COSTA RICA

April 2002

6 of 7

COSTA RICA

April 2002

6 of 7

We sleep late to recover from the night before. We have plans to make another hike with Julio tonight, so we

decide to take just a short walk in the early afternoon with Roberto.

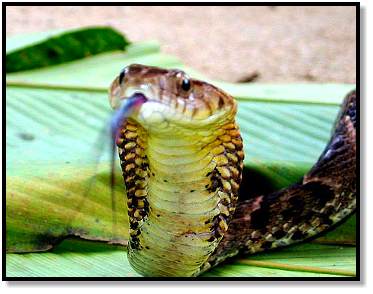

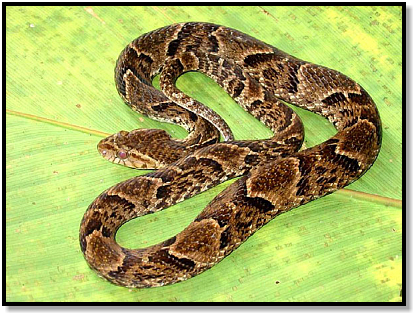

As we approach the trail, a movement catches my eye, a train of fast-moving brown triangles. “Fer-de-Lance!” I

cry. “No!” yells Roberto as the snake dives down a hole beneath the roots of a tree. “It’s a mimic,” he says. “At least, I

think so.”

Roberto takes a twig and pushes it down the hole. “I can feel it.” Then he blindly sticks his hand down there (!?)

and in a moment pulls out this angry, striking snake that maybe is, maybe isn’t, a Fer-de-Lance. As the snake bites

him, Roberto speculates, “Let’s see if I’m right.”

Fortunately, it’s a False Fer-de-Lance. What made Roberto confident enough to grab, despite barely a glance,

before the snake disappeared? Must have been equal parts experience and the kind of abandon that infects hard-core

herpers, even scientists.

The snake rewards us with a nice show of hissing and neck flaring, pretending he’s a cobra, before settling down

into a relaxed pose.

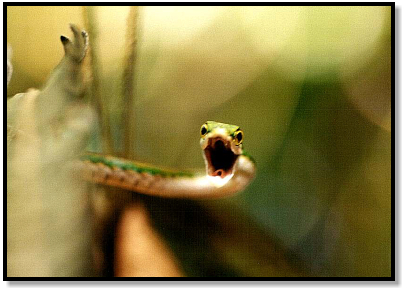

While we’re taking photos someone approaches and asks if we want to see something he’s found. Apparently

word has gotten around that we are interested in seeing snakes, and this person was nice enough to catch one for us to

photograph. It’s a diferent species of Parrot Snake, a small, slender serpent with a big mouth.

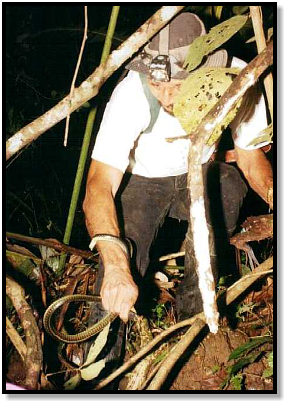

That evening we pick up Julio again and drive another few hours towards the Caribbean coast. This time,

instead of steep mountains, we hike the soft, sandy bottom of a lowlands stream bed, shining our lights along the

banks and in the branches of overhanging trees. We quickly find a Brown Blunt-Headed Tree Snake among some

cane, and a Mexican Tree Frog perched on a large leaf.

A few moments later Julio stops and fixes his light on some leaves high in the air, maybe 30 feet up. He points to

a fingernail sliver of white just barely visible over the edge of a branch. It’s the belly of a sleeping snake, he explains.

How did he spot it, when we can barely see it even with someone pointing it out?

The snake is far out of reach, way too high and at the end of thin branches that can’t be climbed, so we prepare

to move ahead. Except for Julio. Instead, he takes out his machete, scans the stream bank and selects a straight-

looking sapling. A few whacks later he has a handful of heavy sticks, like two-foot batons.

Julio moves to the center of the stream and looks up to where our flashlights have spotlighted the few inches of

snake belly. He grips one end of a stick, cocks his arm, and lets it fly. With a whirrr the baton goes flying end-over-end

through the darkness and strikes the exact branch, 30 feet above our heads, only inches from the startled snake! Then

he does it again . . . and again . . . each time avoiding a direct hit on the snake itself, causing it to slip and fall lower, as

Julio keeps throwing perfect strikes at the supporting branches.

But eventually the fleeing snake lands where it is obscured by lower branches and the sticks cannot find their

target. Back to the machete. Julio chops down the 20’ leaf of a giant heliconia, strips away everything but the stiff

center rib, and cuts a notch at the end. He climbs up the tree, and with his improvised pole being just the right length,

Julio prods the snake, trying to flip it into the stream below where the rest of us are waiting to catch it. Instead, it

climbs lower to the larger, steadier branches where Julio is standing, so he reaches out and finally gets it in hand.

The snake turns out to be an Ebony Keelback, a nonvenomous colubrid with very smooth scales. Although

usually black on top, this specimen is more grayish-green.

We continue wading down the stream and Julio spots another sleeping snake, this time a Parrot Snake that’s

even higher up than the Keelback. Once again, his arm and aim are extraordinary, and the snake is knocked loose

from its branch, free-falling towards the stream below. But with a remarkable save on the way down, the snake snags

its tail on the tip of a branch, dangles for a moment, then manages to crawl up and away out of reach. We are

disappointed, but not for long.

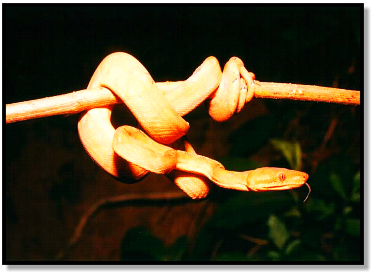

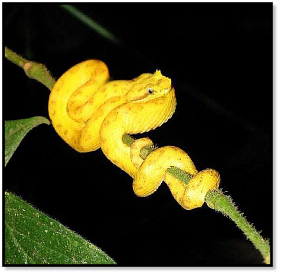

Just around the bend Julio picks up the golden eye-shine of a small snake crawling along a branch above the

stream, but this time within easy reach.

I climb up the bank, reach into the branches, and come down with a gorgeous Tree Boa.

At the next bend the stream becomes a bit deeper, so we walk a while on the bank. I almost step on this juvenile

Hog-Nose Viper lying in ambush for frogs and lizards on top of the leaf litter.

Within minutes we find another snake searching for food along the banks of the stream, a Cat-Eyed Snake.

Earlier on I had completely embarrassed myself in front of the others. We had come upon a female Emerald

Basilisk that was sleeping on a low branch above the stream, and I was given the honor of making the guaranteed

catch.

She didn’t move or open an eye as I slowly walked up to her, but then just before grabbing, I hesitated. That was

enough ― the lizard dived right into the water and was gone. My fellow herpers immediately proclaimed it the worst

capture attempt ever seen, as they were happy to remind me every 15 minutes or so. But they were right; it truly was

pathetic.

Fortunately, I’m presented with an opportunity to redeem myself when we find another sleeping basilisk. This

time I boldly step forward and grab the lizard before it gets away, and I am welcomed back as a productive member of

society.

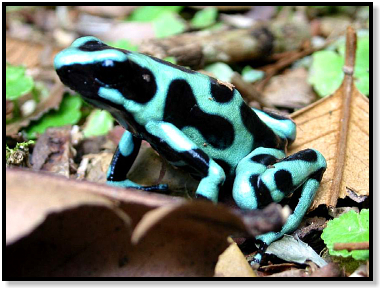

The next catch further advances my rehabilitation. We climb up on the stream bank to bypass a deep stretch of

water, and I notice some movement off to the side. Turning my headlamp, I’m surprised to see a black-and-green frog

hopping away. “Auratus!” I call out to the others while crashing through the underbrush to grab the little guy.

This is a real surprise, because we weren’t expecting to find any other dart frogs during our trip, except for the

Strawberry/Blue Jeans Dart Frogs that are everywhere. Instead, we come up with a different species, one not

commonly found in this part of the country.

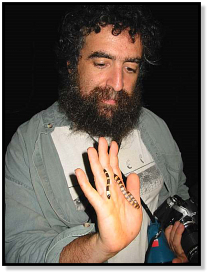

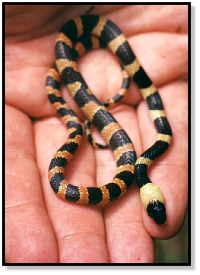

We leave the stream and everyone is still shining the branches for arboreal snakes, except for Ron, who is

thinking about Fer-de-Lance and watching his feet. So as he walks behind Julio and Roberto, Ron suddenly stops at a

spot they’ve just passed, and calls out, “Snake!” He holds his light on our fifth black/red/yellow-banded snake of the

trip, a juvenile Calico Snake.

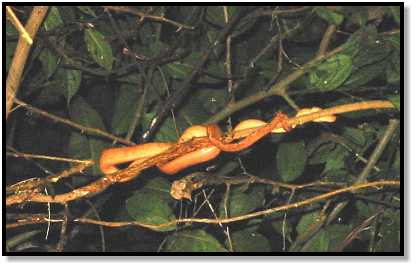

The last snake we find is an Oropel, or gold phase Eyelash Viper, slowly extending itself up a narrow tree.

By now it’s approaching 2:00 am. We drive back to Julio’s house to drop him off, and to see one more snake.

Seems Julio’s oldest son had also been out hunting that night, and he’s brought back something to show us. Julio leads

us to a shack behind his house, carefully pulls back the lid of a wooden box, and reaching in with two snake hooks,

lifts out a giant.

It’s the most majestic snake I have ever seen. Perhaps eight feet long and twice as thick as my arm, with a head

bigger than combined fists, and a presence that concentrates our full attention on the powerful coil in front of us. I can

honestly say that I am not prepared for the indelible impression of my first Bushmaster.

It is quite literally breathtaking. I find myself breathing deeply and staring silently, sometimes blinking my eyes

or slightly shaking my head. I am simply in awe. As Ron puts it, there’s something about standing there without

glass between you and a snake like that.

Annulated Tree Boa

Corallus annulatus

False Fer-de-Lance

Xenodon rabdocephalus

Lined Parrot Snake

Leptophis nebulossa

Ebony Keelback

Chironius grandisquamis

Central American Bushmaster

Lachesis muta stenophrys

Black-And-Green Dart Frog

Dendrobates auratus