COSTA RICA

April 2002

5 of 7

COSTA RICA

April 2002

5 of 7

Wake up early to watch incredible birds: Keel-billed and Chestnut-mandibled Toucans, Scarlet and Red-rumped

Tanagers, parrots, hummingbirds, etc. Then hit the trail, where our first encounter is with . . . a crab. Waving his

claws at us, as if we are a strange thing to find on the floor of a rainforest. Above us dips an enormous damsel fly,

stroking its wings so slowly it appears to be rowing through the air.

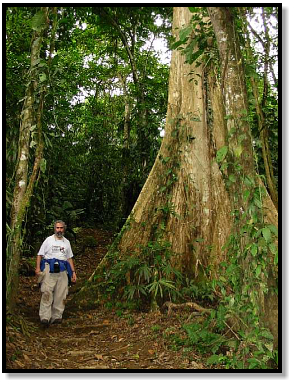

There is so much cover in the rainforest, and the animals are so cryptic, that perhaps the most useful piece of

equipment for herping in the tropics is a good eye. Fortunately, Ron brought two. Usually we’re pretty even in

making good spots, but in Costa Rica he keeps noticing one hard-to-see critter after another, leaving me very

impressed (and a bit envious).

On this morning his eye catches the camo of a Litter Toad, looking like the dead leaves that provide its cover.

A few steps farther up the trail it’s finally my turn to detect a slightly out-of-place pattern mixed in with the leaf

litter.

Something doesn’t look quite right. There’s a small shape that’s a bit too circular, and then I realize, it has a

head. At the end of that head is a pointy nose that also doesn’t look quite right, but that’s why they call these snakes

Hog-Nose Vipers.

This is the first of three that we ultimately find, but while the others are fairly feisty and happy to strike, this one

is quite lethargic. It’s weak, barely attempting to crawl away when we lift it from the trail. And it looks

undernourished, perhaps because of a prey shortage due to drought conditions.

After releasing the snake we walk back towards the station dining hall, pausing now and then to watch howlers

overhead and to take in all the growing things that surround us. Sometimes you just have to stop and smell the

fungus along the way . . . .

We arrive for lunch and are met by Roberto, a local herpetologist who is to be our great companion for the

remainder of the trip. Yesterday he had been out in the field working on a project, so he brings a couple of specimens

for show-and-tell. The first is another black-and-red banded snake (they’ve got a bunch of different kinds down there).

The other is a Black-Tail Tree Boa which is unusually docile and makes no attempt to strike. Surprising,

considering how nasty they usually are.

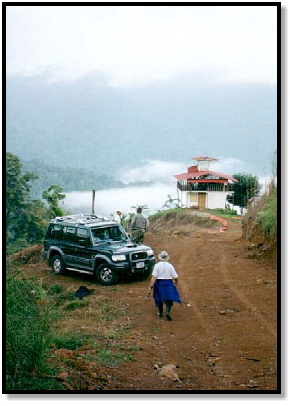

Knowing how eager we are to see our top target, Roberto offers to take us on a night hike into a remote region of

the country that’s prime Bushmaster habitat. We travel far from the lowlands up to a mountainous area, and arrive at

the home of Julio, a campesino who knows where to find the big snakes. We drive another hour deeper into the

backcountry, then hike down a steep valley where we wait by a small stream for darkness to arrive.

Finally, it’s time to move. We start back along the path that took us into the valley, when Julio says, “I hate

trails,” and starts hacking at the vegetation with his machete. Roberto turns to us and says, “That’s what I like about

this guy!” and we have no choice but to follow, breaking all the rules of rainforest hiking.

We plunge into the dense undergrowth, unable to see our feet; forced to grab trees covered with thorns and

crawling with bitey, stingy things; slipping on mossy logs and slick stones, in a near vertical climb straight up the

mountain, searching in darkness for the hemisphere’s largest venomous snake. I recall what I would normally be

doing on a Wednesday night, and quickly conclude that my graduate school classes in Organizational Culture are

never like this.

Our first herp is a common tree frog.

Our next find is a bit more dramatic. I’m walking a few steps behind Roberto; suddenly, he freezes. Julio has

stopped just in front of him. They silently confer, then Roberto bends over, very slowly reaches down, and with his

hands securely in place, calmly pulls up a large female Fer-de-Lance. Seems that it spooked as Julio approached, then

came to rest right by Roberto’s foot! Just in case we need a reminder of what may be underfoot in the rainforest.

And what is Roberto’s first reaction? Not, “Whew, that was close!!” Instead, being a born scientist, he exclaims

“Look at the size of that prey item!” Indeed, there is a huge bulge in this snake, and Roberto is determined to identify

it (“I’ll bet it’s a spiny rat!”). He tries to get the Fer-de-Lance to regurgitate, but the snake is stubborn and holds down

its food. So Roberto, who is equally stubborn, bags the heavy animal and carries it up and down the mountain for the

next four hours, just so he can bring it back to the lab for proper examination.

In the next 15 minutes we come across three more snakes, each a different species. That was one of the most

notable aspects of herping the tropics, the enormous variety. Practically every time we found a snake it was a different

kind. Except for Fer-de-Lance, we logged very few duplicates.

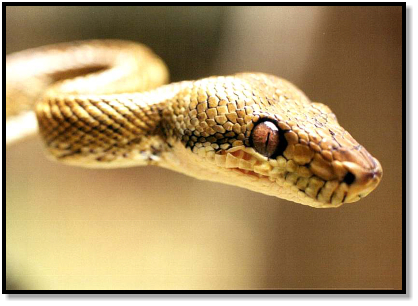

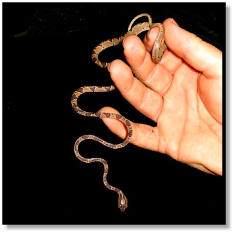

The first of this trio is sleeping in a surprisingly exposed position right on top of a large leaf. It’s yet another

type of tri-color, a Neotropical Snail-Eating Snake. Note the blunt head and undershot jaw, especially adapted for

pulling snails out of their shells.

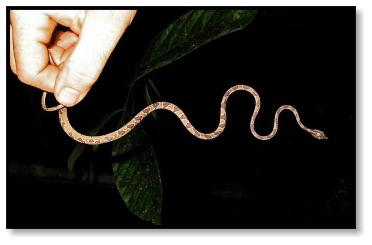

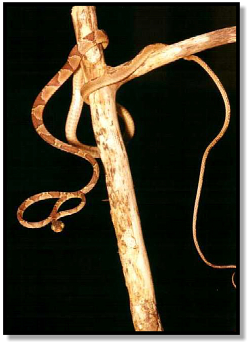

The next snake also has a chunky head, the aptly named Brown Blunt-Headed Vine Snake. These are the

anorexics of the serpent world, skinnier than you can imagine. They glide practically weightless out to the end of the

thinnest twigs to feed on lizards who are sleeping there trying to avoid predators. Imatodes have also evolved an

adaptation of their vertebrae, which lock into position using a special I-beam construction, enabling the snake to

stretch out most of its body length in mid-air while reaching from one branch to another.

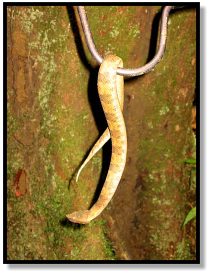

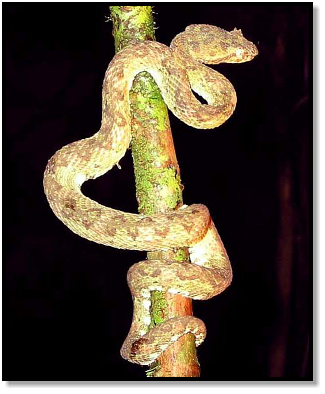

Our other snake is found slowly shimmying up the mossy trunk of a narrow young tree, an arboreal Eyelash

Viper. This species comes in different color variations, from the gold phase (known locally as Oropel) to the “lichen”

phase we find this night, so called for the greenish-brown and reddish blotches along its back.

We’re very pleased with our finds, but Julio is still determined to find us a Bushmaster. Up and down the

mountain we climb, looking beneath plants and between promising tree roots. Around 1:00 AM, after six hours of

strenuous hiking, Julio concedes that it isn’t going to happen. We finally head back to his place, and after dropping

him off we spot our last snake of the night, a Fer-de-Lance crossing the highway around 4:00 AM as we return to the

field station.

Brown Blunt-Headed Vine Snake

Imatodes cenchoa

Litter Toad

Bufo haemetiticus

Hog-Nose Viper

Porthidium nasutum

Calico Snake

Oxyrhopus petolarius

Black-Tail Tree Boa

Corallus ruschenbergerii

Mexican Tree Frog

Smilisca baudinii

Neotropical Snail-Eating Snake

Dipsis bicolor

Eyelash Viper

“lichen” phase

Bothriechis schlegelii