MIDWEST

April 2005

1 of 6

MIDWEST

April 2005

1 of 6

OK, I admit it: I was naïve.

Think of the herping hot spots in the U.S. and what comes to mind? For me it was always southern states

―

Florida, Texas, the Carolinas

―

or out west in Arizona and California. As far as I knew, the prairies in between were

home to cattle and corn; it never occurred to me they might also have herps worth traveling to see.

But one by one, people kept telling me, “You really should check out the Midwest.” I heard stories of snakes that

can be found in staggering numbers, so plentiful they seem to be under every stone; places that actually live up to

their herp-inspired names, and mysterious “snake migrations” that cause roads to close. This kind of herping

sounded different from anything I’d experienced before, so I decided to go see what I’d been missing.

Catch a pre-dawn flight from Newark and I’m herping by noon in a marshy area of Illinois. My excellent

companion is photographer Mike Cravens, and we’re in search of a snake I’ve never seen, the Eastern Massasauga.

Loss of wetlands has endangered these secretive “swamp rattlers” throughout their range, which is limited to the

Midwest (except for small disjunct populations in upstate New York and Ontario). Sightings are uncommon, but the

weather is right and Mike knows what he’s doing, so my hopes are up.

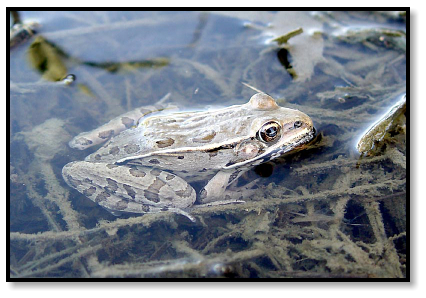

It’s an early Spring and temps have been cool, but Leopard Frogs launch into the water as we approach, and a

couple of Garter Snakes crawl out of our way, a good sign that it’s warm enough for herps to be active on the surface.

We’re walking beside the bog, scanning the grassy edges for something snake-like, when a thick brown stick

catches my eye. Blink twice, noticedthe scaly texture, then follow the S-curve to a triangular head raised slightly above

the ground. There it is

―

my first Massasauga!

It’s a handsome, robust snake, a larger chocolately version of the closely-related Pygmy Rattlesnake, though not

nearly as jittery.

We admire her for some time, then spend the rest of our day exploring abandoned buildings, but find nothing

more exciting than a few Garter Snakes. Part ways after pizza, and the following morning I head towards my next

destination:

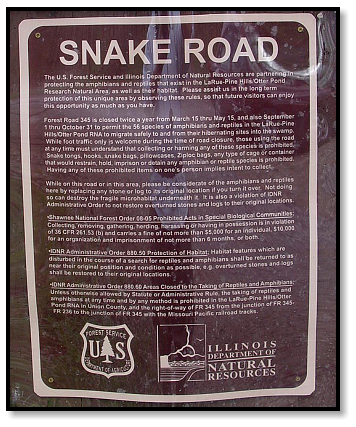

This is a main attraction, a mass migration of serpents. The concept is completely foreign to me.

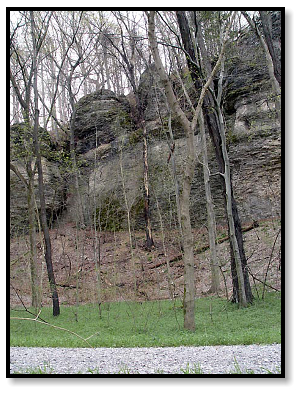

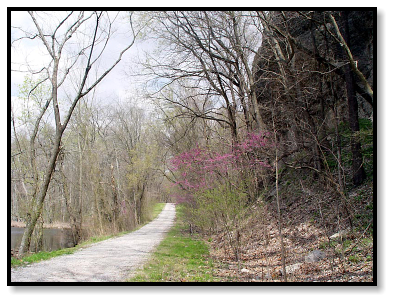

On one side, a series of swamps that shelter a variety of snakes, dominated by Western Cottonmouths.

Opposite, a ragged wall of limestone bluffs rising straight up from the flat forest floor. Between them, a gravel road

that’s closed twice a year for migrating snakes.

In the fall, Cottonmouths and other aquatic species leave the swamps and head for higher elevation, crawling up

to a quarter-mile through woods that separate the water from the rocks. They cross the road (now we know why!) and

climb the cliffs to seek refuge in the limestone, descending deep into the fissures where they will overwinter. These

den sites are shared with Timber Rattlesnakes, Copperheads, Black Ratsnakes, and other species retreating from the

surrounding forest before winter’s invasion. Come spring the migrants reverse direction, leaving the bluffs as the

weather warms, returning to the swamps for summer.

During migrations the road is closed to all vehicles (the only one in the country to do so for snakes, as far as I

know). I’m told that on a good day it’s possible to see dozens of snakes in just a few hours of walking, but

unfortunately, this is not a good day. It’s chilly (in the 50’s), it’s cloudy, but most of all, it’s windy. Very windy. As I

pull up to Snake Road I wonder if I’ll see anything at all.

Park by the gate and just sit in the car. I am the only one there, testimony that inclement weather has postponed

the migration. I’ve arrived too early, before the start of herp (and herper) activity.

As I’m staring through the windshield, trying to decide if it’s worth getting out, I notice a stick on the road about

100 yards past the gate. Did it move? Too far away to tell for sure. I suspect wishful thinking on my part, but

conclude maybe I should try with my glasses on. Still can’t tell. (They’re just reading glasses, not much good for

distance.) Should I break out the binocs, or break out running? Oh, what the hell, I didn’t come all this way just to sit

in the car.

I grab the camera and run towards the stick.

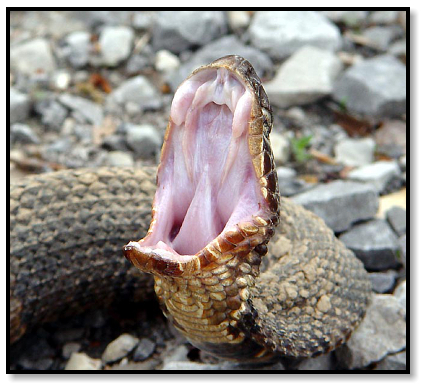

As I move in, it begins to move, too. I now realize it’s a Cottonmouth, and as I catch up it turns to welcome me

with open, uh . . . well, you know.

I’m impressed. Despite the rotten conditions, this hardy Moccasin is determined to uphold the reputation of

Snake Road. The least I can do is reciprocate and ignore the weather as well. Maybe I won’t find many, but perhaps a

few more members of the welcome committee will be waiting for me.

Spend quite a bit of time climbing the bluffs and checking out crevices, but I find nothing in the rocks. Decide

instead to go road cruising in slow motion, walking the gravel and keeping my eyes open for another suspicious-

looking stick. Turns out that keeping my ears open is equally valuable. More than once I hear a rustle in the woods

and discover Cottonmouths on the move. My final one is another long-distance sighting. By the time I reach the spot

where it crawled off the road, the snake had disappeared into the forest, but I track it by sound as it disturbs the crisp,

dry leaves.

In itself, finding Cottonmouths is nothing special

―

I’ve seen many more on other trips

―

but this is very

different. Besides the strangeness of following Water Moccasins in a forest, as if they were woodland wannabes, I’m

aware of just how deliberate their movements are. I can see where they’re coming from, where they’re going, and why

they need to get there. All of them out at the same time, all heading in the same direction, all for the same purpose:

neither foraging nor mating nor thermoregulating individually, but migrating en mass to their summer home. Just

like Arctic Terns returning to the tundra, only a lot slower and closer to the ground. With fangs.

Although I don’t encounter dozens of snakes, I’m not disappointed. I had come to observe the migration, and

while it isn’t in full swing, I am witness to its beginning. And for my first time, that is enough.

To read a more thorough account of migrations at Snake Road, I highly recommend Shawnee Moccasins (The Great Moccasin

Migration) on the excellent website of Mike Pingleton.

Plains Leopard Frog

Rana blairi

Eastern Massasauga

Sistrurus catenatus catenatus

Western Cottonmouth

Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma