MIDWEST

April 2005

5 of 6

MIDWEST

April 2005

5 of 6

The following day Chad leads us into perfect prairie habitat, where we begin with the daily ritual of rocks and

Ringnecks.

One little guy does something I’ve never seen before in this species. He’s on his back, lying perfectly still, putting

his beautiful belly on display. We nudge the snake to see if it’s OK, but it doesn’t move. Minutes pass and I’m

beginning to think it’s injured, perhaps when we lifted the rock, but suddenly it rolls over and zips away. Never heard

of a Ringneck playing “hognose” before, pretending to be dead.

Another rock reveals the largest Skink in North America, hefty and handsome in its herringbone suit, followed

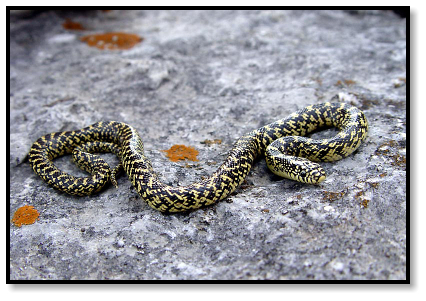

by a juvenile Kingsnake, an intergrade in this region where East meets West.

Then comes a succession of Central Plains Milksnakes, our primary target for the day.

In between we’re also treated to other species:

At first I think this is a juvenile Garter Snake, but it doesn’t look quite right. I ask the others and learn it’s a Lined

Snake, a species I had never even heard of, much less seen before.

No doubt about this next one. Definitely a Garter Snake, and one of the prettiest I’ve ever seen.

Decide to end up where we started the day before, back to viridis hill. Chad comes across another one hidden in

the grass, this time a juvenile that spooks when he approaches . . .

. . . and I find one last Rattlesnake, neatly tucked away in the soft light of the setting sun.

There is something very special about seeing Prairie Rattlesnakes in situ. Other Crotalus may be more impressive

in size (Diamondbacks), beauty (high-yellow Blacktails), or lethal potential (Neotropicals). But in their natural setting

viridis give me a unique impression: a glimpse of the past, of origins, because it was here the family’s most distinctive

feature was formed

―

in these grasslands, some snakes became Rattlesnakes.

According to a leading theory, rattles evolved as an audible defense against large, hoofed mammals that might

trample snakes underfoot if not warned away. This is believed to have originated in the Great Plains, with its huge

herds of bison and its vulnerable serpents. And in this same place I stare at the Rattlesnake before me, barely visible in

the short grass, a tableau from a time that gave rise to the first of its kind.

Great Plains Skink

Eumeces obsoletus

Speckled x Desert Kingsnake intergrade

Lampropeltis getulus holbrooki x L. g. splendida

Central Plains Milksnake

Lampropeltis triangulum gentilis

Great Plains Ratsnake (juvenile)

Pantherophis guttata emoryi

Yellow-Bellied Racer (juvenile)

Coluber constrictor flaviventris

Lined Snake

Tropidoclonion lineatum

Plains Garter Snake

Thamnophis radix